When characters speak, the reader should be trapped in the moment, hooked, not pulled out of the story by unwieldy phrasing, words that simply don’t fit, or punctuation that distracts. When reading your dialogue aloud, which you should always do, if it sticks out or trips you, rework it so that it does what it’s supposed to do. If that doesn’t work, cut it out.

Dialogue must have an objective: advancing plot; increasing tension; developing character. If it doesn’t do any of these, if we don’t learn something about the character, it should be cut. Harsh, but it’s the only way your story will work.

Create a short scene, with two characters, and make it a scenario that carries a high percentage of dialogue.

We use everyday dialogue in real life, but when we’re speaking to a friend, or a sibling, we’re not trying to sell a book or push a reader to turn to the next page. That’s why all fiction dialogue must be filled with intention; an action or reaction to further an objective.

When an obstacle is placed in front of an objective, conflict arises. This conflict will ensure dynamic because it heightens tension. Tension lifts the story from the everyday and keeps your reader hooked because they like to see characters challenged. It’s the only way a character will change.

In your scene, have one character strive to achieve an objective, with another standing in their way, obstructing progress.

The objective could be as simple as wanting to get into a club, to find friends lost during an earlier pub-crawl, or trying to hire a taxi to get across town to meet a lover, but there’s only one taxi and someone else wants it just as bad (going the other way).

Once A’s objective is being thwarted, the ensuing tension provides loads of scope to use dialogue to convey frustration, spite, fear, passion, need and, of course, sub-text – the underlying meaning of a phrase or statement.

When writing a dialogue-heavy scene, don’t bog your reader down with expository telling. Don’t have your character spew out information that’s already known because you’re afraid your reader will run away if they don’t know what’s going on. Reveal detail in a way that elicits response – action/reaction – short and concise, or at best not dragged out. This rat-tat-tat ups the dynamic and ensures your reader is fully involved. Of course you can’t keep such a pace up forever, but in a short scene, there’s no point in long flowing speeches full of information that will drive your reader into the kitchen. Keep it terse and crisp.

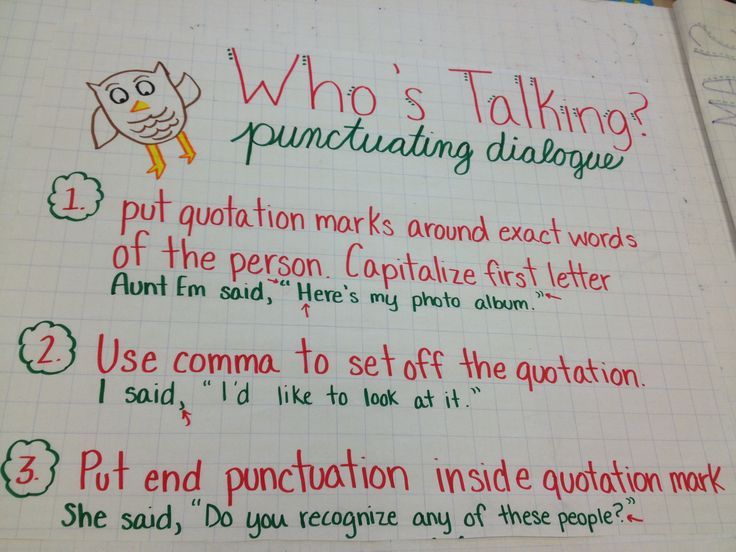

In order to convey such a scene so that it will be fully understood by your reader, an accepted standard of punctuation must be adhered to. While there are more complex rules of style, the few basics will get you through any club door or into any taxi. It’s just about remembering what goes where.

Write your scene, and don’t worry about being right or wrong. Once the scene is written, you can view the dialogue rules and apply them in your second draft.

First rule: The complete spoken phrase is enclosed in quotation marks. This includes your full stop, comma, exclamation mark, or question mark. The dialogue tag that follows is still part of the dialogue equation, so the first word is not capitalised unless it is a personal pronoun (‘I’ – John/Mary).

“I need to get in to find my friends,” Mary said.

Or – Mary looked at the bouncer, steadying herself against the pillar. “I need to get in to find my friends.”

If you place the dialogue tag before the dialogue, the comma goes before the quotation marks…

He stared at her, as if she was something he’d wiped off his shoe, and said, “Sorry, love, not a chance.”

You can also have it as a discontinued phrase, placing a description/action tag between dialogue beats. –

“Sorry, love,” he replied, staring at her as if she was something he’d wiped off his shoe, “not a chance.”

You could also have this as two complete sentences, with the first dialogue phrase ending in a comma, but with the following observation tag ending in a full stop.

“Sorry, love,” he replied, staring at her as if she was something he’d wiped off his shoe. “Not a chance.”

An em-dash (named because the dash is the length of an m) denotes interrupted dialogue. There’s no need to explain the interruption because the m-dash is an accepted convention.

“Look, love, I already told–”

“But you don’t understand. I have to–”

“Don’t interrupt me, love.” He straight-armed her away from the door. “I told you you’re not getting in.”

When a character’s dialogue trails off, an ellipsis is used. It contains three dots before the quotation mark, or next word or thought.

“But you don’t understand. I need to…” Shit, what am I going to do?

“But you don’t understand. I need to… Shit, what am I going to do?”

Readers like to know who is speaking, so it’s not good practice to reveal the speaker’s identity at the end of a paragraph or several sentences. Such ‘hanging’ dialogue tags create imbalance. Consider these examples…

“I won’t have it. You’ve known me over a year now and you won’t get away with treating me as if I’ve just turned up begging your last penny from you,” Frank said, his face a deep red.

“I won’t have it,” Frank said, his face a deep red. “You’ve known me over a year now and you won’t get away with treating me as if I’ve just turned up begging your last penny from you.”

The second example works for me because it reveals the speaker after the first clause/sentence so I don’t have to guess, and the paragraph isn’t weighted down by that dialogue tag at the end.

Be sure to separate each character’s dialogue into a new paragraph. This makes it easy for your readers to distinguish who the speaker is.

Said-bookisms are where a writer uses something other than said in a dialogue tag. Your reader is blind to ‘said’, once it’s not used in a series. Their focus remains exclusively on the story. You don’t have to use it all the time because you’ll be using pre and post-dialogue action tags, or untagged dialogue where the identity is unambiguous. To be extreme, the likes of replied, answered, asked, told, and remarked are acceptable, but most others like snarled, laughed, responded, snapped, elucidated, etc., etc., pull your reader from the story because of their telling and redundant nature.

So, with that in mind, only use dialogue tags that denote speech. “The joke’s on you,” she laughed – is not acceptable, because you cannot laugh dialogue, or at least not in a manner that will be understood. Considered writing will get you places. The first draft is the place to make such mistakes, whereas the second-on is the arena for revision and putting things right.

Make every word count. Have confidence in your writing, and never be afraid to tweak and revise as needs be. The tighter your writing, the less work your editor has to do. If you have any questions, feel free to pop them below and I’ll do my best to answer.